17 Aug Which Bible Translation is the Best?

One could easily be overwhelmed and confused by the many different translations available these days.

The Scriptures were originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, which makes translation necessary—but why are there so many? And are they really all that different? Is one better than another?

There are several factors that have contributed to the assortment of translations at our fingertips today. The first, and possibly most important factor, has to do with the original Hebrew, Greek, or Aramaic manuscripts from which translators are working. The English translations we have today are based off of these original manuscripts found throughout the years. The better shape of the original manuscript and the quantity of manuscripts, the better the base from which to translate.

A second key factor at play is the receptor language, or language into which the Bible is being translated. As scholars labor to translate these original manuscripts, they must consider how to convey the original language with all of its cultural words, expressions, and meanings into a different language that often does not have the same words, expressions, or meanings. For example, in the Ancient Near Eastern culture, “intestines” was frequently used to describe the factory of one’s emotions and affections, much like we use “our heart” today. The challenge for scholars is to do this in a way that does not distort the original text but at the same time translates it in a way that is clear, understandable, and relevant to the reader. In a recent article on translation, scholar N.T. Wright stated, “Translation is bound to distort. But not to translate, and not to upgrade English translations quite frequently, is to collude with a different and perhaps worse kind of distortion. Yesterday’s words may sound fine, but they may not say any longer what they used to say.”

Wright’s quote obviously raises the question of the possibility for errors or distortion in our Bibles. Scholars today have more resources available than they did many years ago, which make better, truer translations possible. Nevertheless, the fact remains that no translation is infallible. Errors in translation are inevitable. That does not, however, negate the fact that Scripture, in its original form, is without error. Though our translations today may have errors, readers can be confident that these errors are cosmetic in nature, not doctrinal.

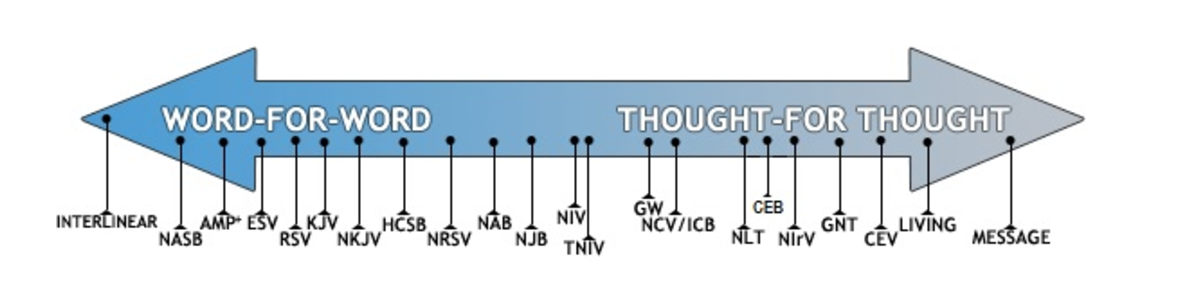

So how does one choose a good, reliable translation? Most translations fall into one of three categories based upon how they were translated. First, there is a formal, or word-for-word, translation. Scholars who attempt to remain as close to the original form of the Hebrew and Greek in both words and grammar have translated Bibles that fall into this category such as the KJV, ESV, and NASB. Second, there is a functional, or thought-for-thought translation. A functional translation attempts to keep the meaning of the original text while putting it into words and expressions that are more normal to the language into which they are translating. The NLT and NIV are found within this category. Finally, there is the free, or paraphrase, translation which attempts to translate ideas from one language to another but does not focus as much on using the exact words of the original. This category includes The Message and the Living Bible.

A few churches and denominations claim that the KJV translation is superior and the only translation that can be trusted. The King James Version was originally written in 1611 after King James commissioned a group of scholars to produce a new translation. Upon its production, King James declared the KJV to be the sole Bible to be used in public worship services in the Church of England. Some today believe that it is the only holy Bible, which is in essence stating that the only true Scripture has been written in English—an arrogant claim.

There is much to be gained by reading and studying various translations. The NLT or the NIV is a good choice for regular reading and when reading large quantities of Scripture. For instance, Grace Church has chosen to teach from the NLT because of the intentionality of its translators in writing it to be read aloud and to make it as accessible as possible to those who hear Scripture. We believe this serves us well for teaching on Sunday morning to an audience that includes people from all aspects of the spiritual maturity spectrum. However, while we do choose to use the NLT in teaching, we encourage you to supplement this thought-for-thought translation with a word-for-word translation, like ESV or NASB, for greater study. Understanding the difference between reading the Bible for longer periods of time (i.e. through an entire NT book) like you would a novel, and studying a passage or series of verses by dissecting it word for word is critical.

“When people ask me which version of the Bible they should use, I have for many years told them that I don’t much mind as long as they always have at least two open on the desk.” —N.T. Wright

Biblegateway.com is a great tool that allows a student of Scripture to read from up to five different translations at once. For further reading on the topic of translations and better Bible studying habits, check out How To Read The Bible For All Its Worth, by Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart.